Fall Bird Migration Guide: Why Birds Fly South & Species to Watch

What if I told you that billions of birds are secretly flying overhead right now, navigating using quantum physics and magnetic fields that humans can’t even detect? Every fall, these remarkable creatures embark on one of nature’s most extraordinary journeys—traveling thousands of miles using navigation systems that make our GPS technology look primitive by comparison.

The autumn wind is smell of falling leaves and pumpkin spice and it also informs us that a major natural event is about to begin. When you are taking your apple cider and plotting your Halloween costumes, billions of birds are preparing to need to travel vast distances, cross continents with an accuracy scientifically unknown to us.

The second part of a cycle that has been taking place over a millennium is fall bird migration. Birds fly away to avoid the cold winter. However, it is not merely a matter of keeping warm, the excursions are life-saving operations that are instigated by complicated biology, environmental clues and navigation skills that are so sophisticated that even quantum physics is involved.

What is the Fall Bird Migration and When Does It really start?

Fall migration is not identical with months that we consider fall. It is fall in human minds because September to November, but the birds begin to move in the middle of summer, and continue on to the so-called early winter.

The initial birds begin their journey at the end of June and the beginning of July. Adult shorebirds abandon their Arctic nesting areas. They are able to fly before their babies can fly since they can eat. Awaiting favorable weather and food on the road south.

During mid July, additional shorebirds congregate at coasts and wetlands. They go south since insects are abundant in the north that provides them with food. Sandpipers and least sandpipers now appear in great flocks and the first actual migration is made.

Purple martins and other swallows are at their highest in August. When there are still numerous insects, they drive away. First the adult martins fly away and then smaller martins fly away after learning to fly by themselves.

Most of the people believe that actual fall migration begins in September. There are warblers, vireos, throbs, and other songbirds flying in the air. They switch color, cease to breed and accumulate additional fat to travel long distances.

Raptor migration is observed during October. The use of warm air rises allows the Hawks, eagles and falcons fly down south. The broad-winged hawks frequently circle about in masses that resemble large birds clouds. They move by gliding rather than by flapping, which conserves energy.

The final high wave is November. Ducks, geese and swans follow ancient flight paths. They travel in the V-shape so that they are not dragged by the wind, which enables them to travel longer distances with the same amount of energy.

The Science Behind Migration: Reason why birds do fly south.

The mere reason that birds fly south to escape cold is only the tip of an iceberg. But the reality is even more complicated and it includes evolution, food and programming so that birds almost appear to know what is going to happen.

Migration is caused more by food than temperature. A lot of birds are also able to cope with the freezing conditions provided there is food left. It is the trouble that when the air cools down, the insects perish or hibernate, the seeds are covered, and the fruit is frozen or impoverished. The birds that experience this food fall are left with two options; adjust to the new environment or relocate to where the food remains good.

When a bird remains in the north during winter, it will run the risk of starvation. Even then it survives it comes in the spring weak, resulting in fewer babies. Those birds which fly south get plenty of food, come back with their heads in the air, and get more babies. This has developed migration into the genes of the birds over a long period of time that spans several generations.

Migration is not only aimed at seeking food but also exploiting the finest of a full year. In the north, summer is long, with less competition among birds, and plenty of insects in a brief hot summer. Birds practically alternate two homes, in each of which they provide benefits to survive and produce the babies.

The birds initiate their trip responding to the changes of daylight. Their brains are equipped with special sensors that sense minute variations in the length of the days. As days become shorter, hormones change and initiate large body transformation putting them in the state to fly.

In the process of the shift, a hormone known as prolactin is reduced and the stress hormone corticosterone is increased. Birds then consume much more, 40 percent more foods. They work the additional calories into fat to be used at a later date and shrivel a part of their bodies to make them lighter and their wing muscles become strong enough to help fly long distances.

The Marvellous Navigation Systems: The Way in which Birds Find their Way.

There are numerous means by which birds get their way. They observe the sun when it rises, and they have a clock therein which informs of the time of sunrise. This assists them to modify their course every hour.

At night they make use of stars when the sun is setting. Little birds are taught the stars during their first summer, and they always know how the sky changes each night. The north star is significant, and they follow the entire pattern to maintain their course.

Flying long distance through special ability of seeing the magnetic field of the earth. Proteins that are present in their eyes, known as cryptochromes, react to blue light and form a pair of electrons in a quantum connection. This connection helps birds to read magnetic north and south and makes a light color or shade which varies according to direction. They have an ability to identify tiny magnetic bumps, hence they fly just like GPS.

Research published in Nature confirmed that the cryptochrome-4 protein found in migratory bird eyes displays quantum mechanical properties that make it sensitive to Earth’s magnetic field. Scientists at the University of Oldenburg demonstrated that European Robin Cry4a showed the largest magnetic sensitivity compared to non-migratory birds, suggesting evolution optimized this protein for navigation.

New research indicates that birds may also perceive very low sounds such as those caused by waves in the ocean or rocks of mountains and utilize the same as maps that span a long distance of miles. They can also smell locations and scent is used to locate a land or particular features.

The Timeline: Month-by-Month Migration.

July: The Silent Beginning

As individuals remain on the beaches, the pioneer migratory birds have already moved. After they are done with their breeding, adult shorebirds begin their journey by the time their offspring are proper to leave. Food and better weather to the north of their start see them have a good time.

These adults do not abandon their homes. They have a schedule that allows them to rest at the places where they are able to change their dead feathers with new ones and they also feed sufficiently to cover the distance. The locations are the main rest and refueling checkpoints.

August: Building Momentum

August is the month when the actual flocks of birds begin to appear. In large flocks of them, frequently in the hundreds of thousands, purple martins and swallows go to places where insects remain abundant. They go away when insects are high and continue going as children get to know.

Shorebirds are also in their highest in the month of August, and old and young ones pass along the coast and wetlands. It has numerous species, small sandpipers and large curlews, all having their courses, so the sight is bustling.

September: The Warbler Wave

September is the month of a great show of warblers. These are small colorful songbirds which occur in mixed flocks. Bird enthusiasts become excited when they hear them in winter color which is not the same as colorful spring breeding color.

Warblers go through many places in July and in August at the best. They also get cool air which offers them good tailwinds. When there is a large number of share, they can make it worthy to the birdwatchers since you can find a variety of birds in just one tree.

October: Raptor Spectacular

It is the season of raptors in October. Eagles, Hawks and falcons can travel in warm air without flapping. Their ability is such that they can travel very long distances but with a small amount of body fat content and this is very important to the birds that may be only a few pounds but has to travel thousands of miles.

The most suitable time to watch some hawks is during the middle to late of September although October is the most diverse. And little kestrels and big eagles Bigger each in their own way. Best views are at the places where birds congregate.

Annual counts at Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Pennsylvania average 18,000 raptors over the four-month fall season, with peak one-day counts exceeding 3,000 birds during September when broad-winged hawks dominate the migration.

November: Waterfowl Finale

The great waterfowl come in November. Ducks, geese, and swans fly in a V form thus being 70 percent efficient. The shape allows birds to share the most demanding position in the fleet.

When the ice over-runs the home places to the north, the waterfowl migrate southwards because their water ceases to exist open. This reaches its climax with winter fronts in late October and early November and the massive numbers can be flown through in hours.

Birds to watch: Species Spotlight.

Fall migration can be too much of a thing, even to a veteran. There are species that are remarkable due to their incredible trips, peculiarities of behavior, or simply due to the fact that they can be easily observed by regular people. Such knowledge on these important species makes us experience the entire migration in an enjoyable manner.

Arctic Tern: Ultimate Commuter.

Arctic tern is the most excellent example of long-distance migrant. It covers the greatest annual path of any bird. It lives in Arctic through summer and flies to the Antarctic in summer and spends practically the entire life in the daylight. It travels between 44,000 and 59,000 miles annually which equals approximately two times round the earth.

Research using geolocators tracked Arctic terns from Maine breeding colonies and revealed they traveled an average of 55,250 miles annually. The average spring migration covered 13,988 miles at 472 miles per day, while fall migration averaged 27,168 miles at 296 miles per day, confirming the longest known annual migration of any bird species.

These small birds do not weigh more than four ounces and rely on the magnetic field of the Earth, the sun and the wave patterns to help them locate their way. Their experience is that it takes months in both directions and they don’t have seasons of summer, because they are chasing the day.

Ruby throated Hummingbird: The Impossible Flight.

The ruby throated hummingbird demonstrates what aviation is capable of. It is so tiny, weighing the nickel, that the flight is accomplished in one journey of 18 hours, through a 500-mile stretch of open water. In order to do so, it stores additional fats which give energy to the crossing.

It feeds bitterly before the journey. It flies around hundreds of flowers a week to accumulate fat. Its flying muscles increase in size and efficiency. Certain parts of its body become smaller in order to reduce its weight, and its oxygen carrying capacity increases significantly. The bird is entirely different as it leaves than it was during its breeding period.

When migrating between breeding grounds and Central American wintering areas, Ruby-throated Hummingbirds fly nonstop for 500 miles or more across the Gulf of Mexico. This non-stop flight requires the birds to double their body mass through fat storage before departure.

Blackpoll Warbler: The Marathon Leader.

Although arctic tern flies the farthest, the blackpoll warbler performs the best in comparison to its size. It weighs less than a half an ounce and travels 8090 hours continuously, round trip, 2,000 miles over the ocean between the northeastern North American coast and South America.

A groundbreaking study published in Biology Letters used miniaturized geolocators to provide irrefutable evidence that blackpoll warblers complete an autumn transoceanic migration ranging from 2,270 to 2,770 km, requiring up to 62 hours of non-stop flight. This confirmed one of the most extraordinary migratory feats on the planet for a 12-gram songbird.

It cannot eat, drink or sleep during this flight. It stores a lot of body fat, about 50 percent of the body mass, to store energy as a human being carrying an extra 75 pounds. Its muscles in flight are made very efficient and it reduces its digestive organs to maintain weight. It is aware that it will not require them till having landed.

Sandhill Crane: The Primitive Life-Travellers.

The migration of sandhill cranes began more than two million years ago. Their height is about four feet and 6 feet in wingspan. Their rattling rattle is heard over miles, and their graceful flocks of them fly such pretty cultures that incite the cultures of the people that see them.

Between February and April, more than half a million sandhill cranes gather on Nebraska’s Platte River in one of North America’s most remarkable wildlife spectacles. This stopover site along the Central Flyway has been used for millennia as cranes stage for journeys extending to eastern Siberia.

The young cranes follow the path which their parents showed them, thus the information is transmitted over numerous generations. Cranes have been sustained at important stopover locations such as the Platte River in Nebraska over thousands of years. Preserving these places will ensure that the birds, as well as the ancient migration routes, are preserved.

Watching Place: Major Flyways of North America.

The Flyways indicate that birds do not fly randomly but they use fixed routes. These are the so-called superhighways that have been molded during millions of years, and they possess certain advantages and problems. The knowledge of the flyways enables an observer to know where and when to see migration.

Atlantic Flyway: Eastern Superhighway.

The Atlantic Flyway originates in Greenland and eastern Canada and proceeds down the Atlantic coast to Florida and then southwards. Many species pass through it. The geography focuses the birds in small passages, and this creates excellent opportunities of seeing a large number of birds simultaneously.

The thinnest is Cape May in New Jersey where the bottleneck can be a concentration of birds. The fly way takes into account the Arctic shorebirds to Caribbean warblers. Marshes provide important stopovers, whereas mountains provide raptors with updrafts in order to save energy. The Appalachian Mountains serve as guides to the south.

Mississippi Flyway: River Highway.

The Mississippi Flyway is an assortment of the greatest river system in the continent between Canada and the Gulf of Mexico. The river and its tributaries form a continuous wetland corridor which sustains a variety of birds. The Minnesota to Louisiana floodplains are sources of food and cover.

The flood cycle produces shifting wetlands which sustain numerous species and fields provide additional food. The flyway sustains approximately 40 percent of the migrating waterfowl in North America.

The Central Flyway: Plains Crossroads.

Central Flyway is between central Canada, Texas, and Mexico. It links the Arctic breeding areas to the tropical wintering areas. The Great Plains provide extensive grasslands and wetlands as well as small lakes, which are major refueling areas.

The area is not mountainous and thus, birds can fly freely; however, there are fewer landmarks. They use a greater dependence on stars and magnetic sense and have to be very careful about energy between stopsovers.

Pacific Flyway: West Gateway.

The Pacific Flyway travels along the Pacific coast through Alaska to South America. It takes advantage of the ocean mild climate and coastal mountains. It goes through the tundra of the arctic to the tropical forests and sustains a variety of birds.

Mountains provide soaring birds with the updrafts and the climate is mild to enable late migration. The combination of coastal wetlands and inland valleys allows the varieties of species to utilize the area at various times and increases the migration period.

Help Plan: Establishing Migration-Friendly Spaces.

Anthropogenic alterations to the landscape destroy important stopover locations and cause novel threats to birds. Creating safe places to assist natural habitat and aid in the prosperity of birds can be a large difference in the activities of individual persons.

Native Plant Gardens: Food and Shelter Networks.

:strip_icc()/garden-for-songbirds-ca53222a0c1c40689013c6af4fafc90b.jpg)

Creating a garden friendly to birds is not just about having a feeder. Native plants provide fruits, seeds and insects which the birds require and they provide protection against predators and weather. Choose plants that feed birds at the time of their entire migration period.

Native plant species support larger, more diverse insect communities than non-native species. Research shows that many migratory birds will visit even small patches of native plants scattered across urban, suburban, and rural landscapes, using them as critical stopover habitat during their journeys.

The early fruits such as serviceberries and cherries benefit the birds later in the summer, whereas the late fruits such as dogwoods and viburnums satisfy the birds later. Native flowers also have insects which are food to many migratory birds, particularly flycatchers and warblers. This is to establish a small ecosystem that sustains the complex food chains that the birds rely on.

Hi-Tech Windows Collision Prevention: Removal of Life-Threatening Accidents.

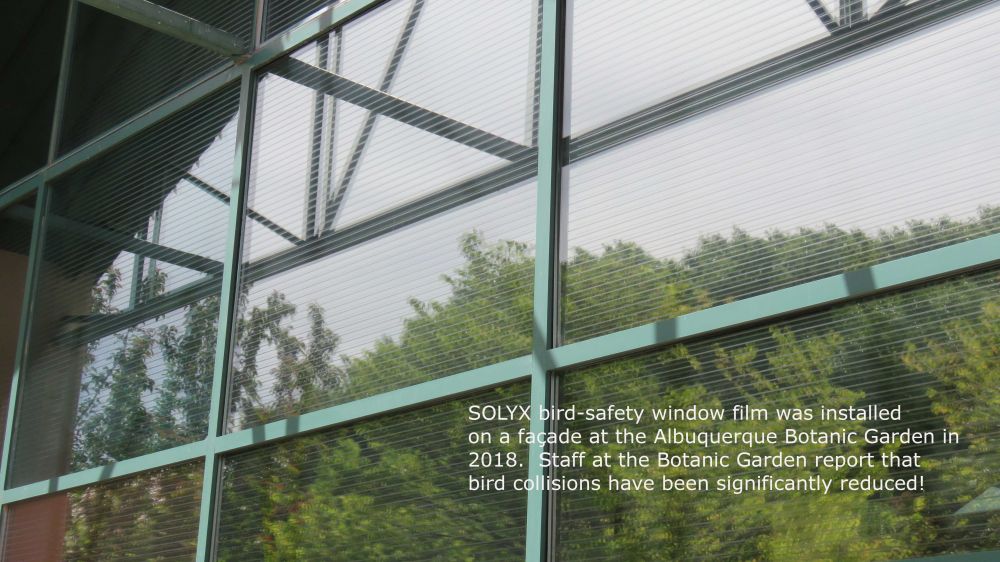

New research published in PLOS ONE uncovered that building collisions kill well over one billion birds annually in the United States. The study examined over 3,000 injured birds and found that only 40 percent survived even with professional rehabilitation care, suggesting current mortality estimates vastly undercount the true toll.

In the United States, hundreds of millions of birds are killed every year because of window collisions. When glass reflects the sky or the land, birds are unable to see it as an obstacle. This risk is aggravated by migration into unfamiliar locations.

Solutions can be of simple and complex nature. Screens or netting eliminate collisions of people but allow people to look out. The reflections are discontinued by films and decals in order to make the birds notice the glass. New UV -reflective designs are typically invisible to humans but visible to birds, which are able to see ultraviolet light.

Recent testing at Chicago’s McCormick Place Convention Center showed that applying dotted film patterns to windows reduced bird collisions by 95 percent. The treatment cost over a million dollars but covered an area equivalent to two football fields, demonstrating the effectiveness of properly spaced visual markers.

Supplementary Food Sources: Feeding Stations.

A clean feeder also provides birds with an added energy, particularly during poor weather when the food around is limited. But feeding needs care. Use clean feeders to prevent sickness and feed with a type that fits the kind of species you are aiming to assist.

Dissimilar seeds are the prey of dissimilar birds. Black oil sunflower seeds are applicable to numerous species. Close relatives and finches are attracted by nyjer (thistle) seed. Sugar-water feeders can be used to refuel hummingbirds on long journeys and Suet provides high-fat food to birds to stock up on it.

The Future of Migration and Climate Change and Conservation.

Climate change is a dynamism whereby the migration is modified forcing birds to adjust to the new environment. Warmer temperature causes breeding areas to extend northwards, migration to extend, and food distribution to shift. These changes are timing issues to birds.

Phenological Mismatches: Temporal Interruptions.

Birds might come when food peaks have elapsed when the plants and insects rise early due to heat. Birds do not rely on food to know it is time to travel to a different place; they rely on the length of the day.

Research published in PNAS found that changing green-up patterns strongly influenced phenological mismatches between bird migration timing and resource availability. The study revealed that birds are experiencing decoupling from the changing phenology of spring vegetation across North America.

Without access to the finest caterpillars, warblers have trouble with raising young. The humming birds might not get any nectar when they do arrive and the seed eaters may not get the plants that have already shed their seeds. This imbalance may cause the starvation of birds despite the presence of food.

New Destinations and Routes: Range Shifts.

Other birds fly northward; others shorten southwards. They also encounter new predators as well as new food, and new challenges emerge because they are flying into new areas.

Others stay longer north during winter and some lengthen their trip to seek favourable habitat. Such transformations are swift in birds, and slow in human beings. Protection of existing critical sites and possible new ones should be done in conservation due to changes in ranges.

Adaptation Strategies: Evolutionary Responses.

There are species, which adapt rapidly to the changes and exhibit new migration patterns or time. As an example, blackcap warblers of Europe winter in Britain, something they did not do in the Mediterranean. These variations indicate genetic alterations in terms of navigation and time.

Knowledge of which species can evolve rapidly and those that cannot, contributes to the priority of conservation.

Summary: The End: The View of one of the greatest shows in nature.

One of the most spectacular events on the earth is the fall bird migration. When we look at thousands of birds flying together, we even hear cranes calling, and when we see hummingbirds refueling in a garden we are reminded of something we know is old and strong which connects us to the planet.

On September 25, 2025, BirdCast detected a record-breaking night when more than 1.2 billion birds streamed south—the largest single-night total ever recorded. This event captured approximately 10 percent of the continent’s birds in flight simultaneously, demonstrating the immense scale of migration occurring overhead.

Thousands of miles are flown by birds without stopping and they time their journeys to the minute across generations at an ounce or so. Through their travels, we are linked to the natural cycles of a long duration and we are reminded of our involvement in maintaining these old tracks.

You see on a fall day you have birds flying over your head. They can be going in their world flight, or little warblers on their way south. They are not merely traveling; it is in a way life that connects their movement with the world of millions of years of history. Next time you encounter a V-formation or you hear cranes screaming in the distance, you know you are looking at a very beautiful and long-lasting system that has been in operation over thousands of generations. Fall migration is a constant marvel that links us with nature and the wonderful world we inhabit in a changing world.

Sources:

Scientific American – How Migrating Birds Use Quantum Effects to Navigate

Audubon Seabird Institute – Arctic Tern Migration Research

Biology Letters – Transoceanic Migration by 12g Songbird

American Bird Conservancy – Building Collisions Study 2024

NPR – Bird Migration Collisions Glass Buildings

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary – Autumn Hawk Migration

PNAS – Decoupling of Bird Migration from Changing Phenology

National Audubon Society – Native Plants Fuel for Migratory Birds

American Bird Conservancy – North American Bird Flyways

Cornell Lab of Ornithology – Record Breaking Night Bird Migration

Nebraska Game & Parks – Sandhill Cranes

Nature – Magnetic Sensitivity Cryptochrome 4

All About Birds – Ruby-throated Hummingbird